|

The post below was first published on November 9, 2016, on the Institute's previous webpage, and has been slightly adapted. Not very different from the morning after a tornado or hurricane blasts through a community, Americans from all sides of the political and theological terrain this morning wake up both to assess damage done, and also, who and what has survived. Like in the aftermath of a disaster, you may be surprised by who has come through seemingly unscathed as well as who has came through significantly wounded. Already, faith-based leaders have reached out to ICTG asking for advice on how to attend to the “election trauma” in and around their congregations. Schools and businesses are facing similar questions related to their staffs, students, and constituents. These requests are not entirely surprising after seeing the remarkable election results [of 2016]. Vote tallies confirm our country is nearly equally split, not in only one or two key states but in a majority of states. We are a divided country. And that remains the case four years later.

Whoever you voted for, wherever is your political home, we each wake up this morning with an imperative to get to know our neighbor more and to understand more of what they felt was most at stake in the [2016] election so we may attend more adequately to one another. The imperative is not just because, after all, so many people feel right now they did not actually know their fellow citizens well or what mattered most to them. No, we must get to know one another more because a vast number of our fellow citizens are wounded today [in 2016]. If we do not attend to these wounds now, the wounds within our country only continue to fester. And now, in 2021, we bear witness to some of the ways they have festered. We also bear witness to the ways the prejudices and biases coursing through our country have been degrading our democracy. Traumatologists know well, we cannot simply move on after severe losses or sudden and remarkable gains. We cannot simply forget the stress these experiences cause among individuals and groups of people. We cannot simply pretend the vast numbers of wounded are not really wounded. Congregations, schools, businesses, and community-based groups can play significant roles in the restorative work needed in the coming weeks. Here are a few things to keep in mind:

0 Comments

This post was first published in the blog series “Teaching and Traumatic Events” on the website of the Wabash Center for Teaching and Learning in Theology and Religion and is shared here with permission. We can define the syllabus with precision, but our best-laid plans are subject to the moments when life simply happens. Questions arise. Frustrations are felt. And the sages on the stage better have something to show for all their high-falutin’ learning. At least this is how I feel when teaching in the midst of traumatic events. I can usually triage the syllabus—shuffling assignments around to give space to the moment. I even know well enough to leave room for the inevitable crisis within my course planning. But what do you actually do when you’re in front of students who have come to class just as raw as you? There’s no media bulletin that will solve the problem. Trauma doesn’t care about public relations. There’s no master lecture that will bring a master solution. Trauma doesn’t leave room for satisfying answers. But I’m here to tell you that all is not lost. Every Christmas break, I go home to Houston. My most recent trip was the first time I had been since Hurricane Harvey. And in the days following my return to Pennsylvania, friends wanted to know what I saw. I didn’t have much to respond with except for the watchwords of the human story. We rebuild. We heal. We grow. We learn. This is what we do in the face of natural disaster. It too is what we can do in the face of psychosocial trauma. But it’s going to take some time. Unfortunately, I have found myself in the position of consulting a number of institutions enduring the perpetration of prejudicial affronts, most frequently concerning rampant sexism, homophobia, and racism. The biggest mistake I see is the grab for a big fix or antidote to make the situation go away. I have to explain that trauma is an immediate crisis that takes hold of us for the long haul, so our job is to equip our communities to rebuild, heal, grow, and learn as best as we can manage, moment by moment, day by day. For teachers, this means reminding ourselves and our students that the more we know, the better we can manage the crisis before us. When life happens, I tell myself to adhere to the following protocol step by step. Gather your composure. Find your footing even in the midst of your insecurity. Claim your own humanity—the right to feel, the right to hurt, the right to grieve. Eat nutrient-rich foods. Drink plenty of water. Meditate, do jumping jacks, practice yoga, or walk around the block. Your first step is to regain your sense of self. Reconnect. Take a moment to let a trusted colleague or companion know that you’re about to go into the fray. You have a community. A simple text message or phone call can remind you that you’re not alone. Lower the bar. When it’s go time, your job today is to “be you” and “do you” with the students. This will equip them with the confidence to do the same. Before you know it, you will fall back into the role of teacher. They will fall back into the role of student. And you’ll together develop a new stasis. Preach what you have practiced. Have your students take a few minutes to do a version of what you have just done. Lead them in a moment of silence or even a quick stretch-break. Let people grab a drink of water and return to class. Let them check in with each other as they trickle back into the room. Your acknowledgment of their humanity will go a long way in garnering the trust you’ll need for the day. Teach the moment. Present what you understand about the situation and contextualize it in light of what you know as teacher-scholar. Then take a few moments to show how you’re learning. In so doing, you’ll remind students that they are not the sum of their emotions. They are also learners with skills and proficiencies to help them grapple with the day beyond what they could have done prior to class. It also solidifies a basis for community-building amidst the new state of affairs. From here, you have a “we” with which to work. Come together around a whiteboard and make a list of questions that you all want to pursue as a class. Name the resources you might consult in the coming days in your search for more information. Excavate your syllabus to see not whether there’s anything of use, but what can be used in the moments ahead. Better questions lead to better possibilities. The work you have put in—together— will bear fruit in the days to come. I know now what else to ask for in the midst of trauma. But until then, use the learning process as a vehicle to position yourselves in renewed strength and community.

This post, written by Rev. Dr. Kate Wiebe, originally was published March 28, 2019, on the ICTG blog. Following a death, a shadow often stretches across what can feel like a long valley in life. Sure, there are times when our neighbors or loved ones live long and vibrant lives. There are those people living in “blue zones” in the world, for example, who tend to die in their sleep, often . Their loved ones celebrate their life well-lived. More often than not, though, death comes with little, if any, warning. Death grieves our spirits, individually and collectively. Sometimes, even, death wrenches our hearts in traumatic ways. Incredibly, human beings possess a seemingly miraculous ability to heal after trauma. Often involuntarily and naturally, we conduct a process of metabolizing the energy of our loss(es), identifying resources, and, even, growing through the aftermath of tragedy. Though this process occurs through individuals, it also appears to function best in concert with survivors perceiving care from others along the way. In particular, care that bears witness to grieving and healing processes appear to be most effective for instigating personal healing processes. Amazingly, it does not seem to matter much who extends care, as long as care is extended. In particular, care that bears witness to grieving and healing processes appear to be most effective for instigating personal healing processes. Care may be expressed by strangers, like when Peter Levine experienced the care of a bystander after a car hit him suddenly when he moved through a crosswalk. Care may be expressed by small groups of close friends or family, like in Blue Zone areas as researched and described by Dan Buettner and National Geographic. Care may be expressed by professionals or peer counselors, like in cases where therapists conduct EMDR, psychological first aid, trauma-informed pastoral counseling, or trauma-informed chaplaincy or spiritual direction. Care may be expressed by fellow survivors, like in cases of online or in-person support groups of survivors who have shared traumatic history. “Firehouse families” – a self-proclaimed, precious, and sacred term for the persons who gathered in the firehouse next door to Sandy Hook Elementary School on December 14, 2012 – is one type of group of people who support one another as only they know how based on their shared history. A skilled caregiver journeys alongside, valuing these senses, and, along the way, witnesses with the survivor to the range of resources available to meet whatever need the survivor may sense. Renowned traumatologists, including Peter Levine (2010), Babette Rothschild (2003, 2008), Basel van der Kolk (2014), and Charles Figley (1995), all describe ways in which most effective forms of care after trauma view the survivor as an expert. That is to say, the caregiver highly values how a survivor inherently senses their needs along the Valley of the Shadow of Death, whether that need is to grieve, to postpone grief for a time, to resolve grief, or any other type of need along the way. Survivors sense what they need, in idiosyncratic ways, at their own pace, and even through repetitious, cyclical, or pendulum patterns. A skilled caregiver journeys alongside, valuing these senses, and, along the way, witnesses with the survivor to the range of resources available to meet whatever need the survivor may sense. Today, many survivors are saying that, as a country, we can do much better at valuing the needs and pacing of survivors, particularly those who are surviving violence. For example, following the news that Jeremy Richman, father of Avielle Richman and co-founder of the Avielle Foundation, died by suicide, fellow “firehouse family” member Nelba Marquez-Greene tweeted the following statement: As soon as 12/14 happened we went right to “Newtown Strong”. It was premature and superficial. I wish we would have said and still say, “Newtown Grieves”. There is strength in grieving. We can acknowledge grief, hope and loss together. There are so many expectations on survivors to change the world. You lose a loved one to gun violence/are injured/survive a shooting AND THEN the weight of world change is on your shoulders. You can’t even grieve. Everyone wants so desperately for you to be okay- that you can never, ever say you’re not. I have rarely met a survivor that has NOT thought about being with their lost loved one. It’s real. We are here. This culture is grief averse and our victim support service structure sucks. These are important words for all of us who practice caregiving – whether as teachers, coaches, nonprofit or business leaders, or faith leaders – to hear. Today, many survivors are saying that, as a country, we can do much better at valuing the needs and pacing of survivors, particularly those who are surviving violence. In what ways is your organization or community caring for survivors, valuing what they sense they need, and pointing out resources along the way? We invite you to share best practices in the comments below. If you are looking for ways your organization – whether a school, nonprofit, congregation, or business – can serve survivors with more effective care, contact us. We’d be glad to help you with education, guides, and support. Make a contribution today to help educate community-based and faith-based organizational leaders in developing long-term care for individuals and families impacted by violence.

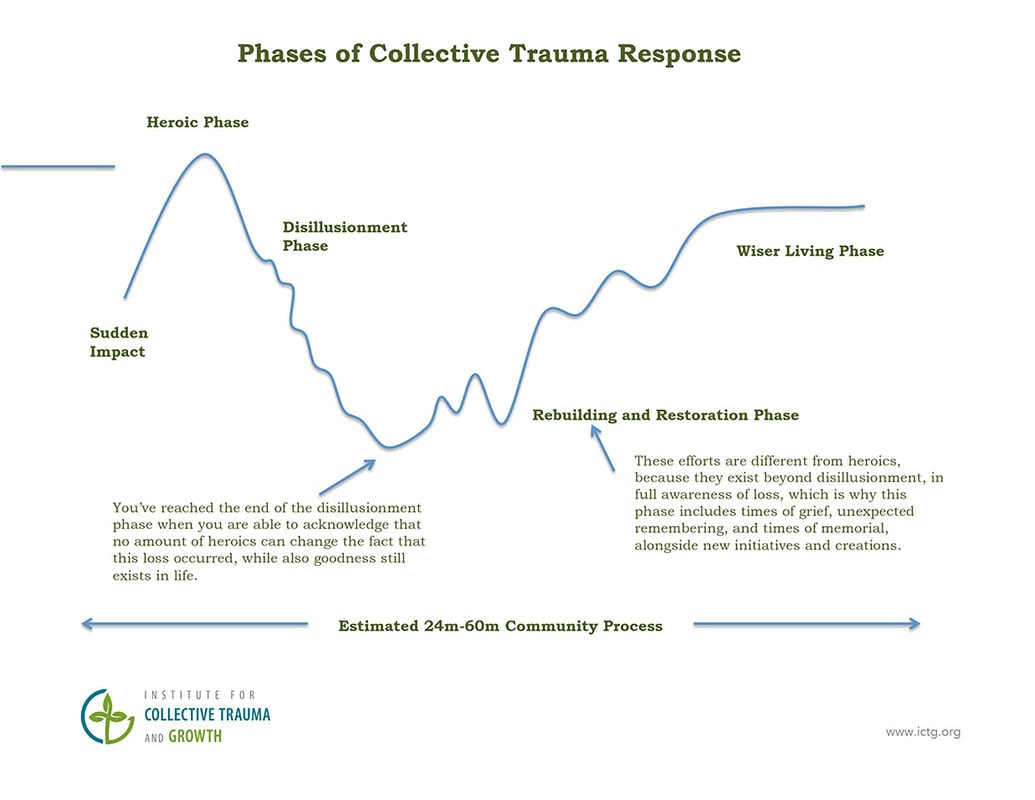

This post, written by Rev. Dr. Kate Wiebe, originally was published April 26, 2019, on the ICTG blog. One of the questions our staff repeatedly receives is: How do we know when we've reached a new phase in disaster response? Several more questions often follow: How do we know if we have reached "disillusionment"? How do we know if we are fully into the rebuilding phase? How do we know if we are healed and have reached a "new normal" or "wiser living" phase? It's helpful to remember the phases are not prescriptive and progressing through them is more of an art than a science. Each group moves through the phases at their own pace and in their own way. Over the years, many people have critiqued the phases – which we encourage! If this chart does not adequately represent your community's experience, then how might you draw it in a way that does? It's meant to be a conversation tool that aids your group in identifying together your own collective experience, while providing a sense of what has generally gone on for others. Each group moves through the phases at their own pace and in their own way. Still, one of the ongoing and more consistent critiques has been how this chart does not adequately represent the long term mental, emotional, and spiritual care needs that appear to persist for many years, perhaps especially following incidents of mass violence, technological disaster, chronic violence, or abuse. The senses of loss of life, loss of community, and loss of trust in fellow human beings can linger for many years. Our colleague, Rev. Matt Crebbin, from the Healing the Healers project often describes healing after human-caused disaster as learning how to dance again, but now with a limp. "We've lost a part of ourselves that we will never get back," he says. At ICTG, we encourage community organizations to host spaces and rituals where survivors can communicate what's happened, express their grief, metabolize their stress or anxiety, and be nourished through their senses of mourning or depression. Recently, the 20th year marker of the Columbine school shooting, as well as recent deaths related to the Sandy Hook and Parkland school shootings, have reminded us all how persistent the senses of disorientation and heartache can be. At ICTG, we encourage community organizations to host spaces and rituals where survivors can communicate what's happened, express their grief, metabolize their stress or anxiety, and be nourished through their senses of mourning or depression. If you'd like to discuss or learn more about how your organization might do that, contact us. We'd be glad to hear from you. Also, you can share helpful tips with others in the comments below about how your community has healed or is continuing in healing.

Many reasons exist why an organization may come to a point of needing to change its internal culture. Some of these include patterns of abuse, patterns of fraud, patterns of betrayal among leadership, or patterns of racism, sexism, or phobias which lead to oppressing certain persons. If your organization is considering ways to change internal culture, here are some questions to help you focus and be effective in making important changes:

Keep in mind that the more specific you can be at the outset in making plans for cultural change, the more effective you can be. There are additional considerations to keep in mind, but these will help any organization begin to create an effective map forward. You can sustain free education, like this blog post, by making a small monthly contribution here. Thank you for your generosity! Rev. Dr. Kate Wiebe serves as the Executive Director of ICTG. She is an organizational health consultant and pastoral psychotherapist. She lives with her family in Santa Barbara, CA.

This post, written by Rev. Dr. Kate Wiebe, originally was published September 24, 2019, on the ICTG blog. When people talk about emergency or disaster preparedness, they most often refer to exit or evacuation strategies, communication plans, and stocking supplies. They rarely, if ever, refer to the mental, emotional, and spiritual practices proven to help survivors thrive beyond adversity. What are these healthful practices? According to researchers like Peter Levine (2012), Bessel van der Kolk (2014), Nadine Burke-Harris (2018), and Nagoski and Nagoski (2019), the keys to thriving beyond adversity are:

... paying attention to how your body feels restored will help you make key decisions about what will sustain you during long-term recovery.

Perhaps what is most compelling about research into the practices that help sustain resiliency is that these acts often are the very elements that make up a community's culture. The food, the dance, the art, the patterns of rest, the family gatherings and neighborly interactions. These are the very things – research is showing – that we ought to embrace in times of crisis and not neglect. In what ways do you or your community maintain healthy cultural practices, even and especially in times of crisis? How have you seen these practices sustain you? Share in the comments below. You can sustain free education, like this blog post, by making a small monthly contribution here. Thank you for your generosity!

As we continue to process in each of our communities the ways that injustices can be addressed and repaired, White persons around you, in your communities, congregations, and teams, or you as a White person, may be re-evaluating systems of racism and wondering what specifically can be done next. Here are some important practices for White persons to consider, for participating in dismantling systems of racism within one's immediate environments: Conduct an Inventory of Relationships

These are only a few of the questions to be asking yourself related to systems of racism in which you may participate, including professional or work environments, local government, literature, and real estate. Make Changes As you review your answers to the questions above, if you found that your numbers are low, what steps can you take to increase the numbers in answer to those questions? Breaking down the insulation that the above questions might reveal requires continual intentional actions in which you see and perceive Persons of Color as genuinely esteemed persons in your life. Not as people in need of your help. Not as people to "enable." Rather, as people to learn from, be guided by, and with whom to partner. As peers and leaders in your life. While it may be relatively easy to increase your reading of Persons of Color authors – and I would encourage you to do that – I would also encourage you to explore the ways you can increase numbers in response to the other questions. This may take harder, or more uncomfortable, work in some cases. It may require having hard conversations with persons in your work, school, congregation, or local real estate arenas. Having these conversations, with thoughtfulness and a focus on listening carefully, are some of the ways you can begin to make a difference. Thank you for being committed to care in the face of ongoing collective trauma. Your care restores. Further reading and additional resources:

Rev. Dr. Kate Wiebe serves as the Executive Director of ICTG. She is an organizational health consultant and pastoral psychotherapist. She lives with her family in Santa Barbara, CA.

This post, written by Rev. Dr. Kate Wiebe, originally was published on September 24, 2019, on the ICTG blog. What is the Village of Care? You likely have heard the adage, "it takes a village to raise a child." Well, in our experience through the mission of the Institute to provide leaders with restorative strategies after collective loss, we find that in most cases it takes a village – a village of care providers – to heal a person or a community after trauma or disaster. Who participates in the Village of Care? Everyone who self-identifies as a common or professional caregiver, including, and not limited to:

Repeatedly and frequently, we hear any one of the above types of persons describe a moment when they felt like the circumstances a person brought to their attention seemed beyond the scope of their expertise or responsibility. For example, a financial advisor recently shared with me about how she wishes she had taken more advantage of psychology course offerings in college, because she often finds her clients sharing with her intimate details about their family or regrets about certain life choices and her being one of the first persons they ever shared those details with. "Making decisions about your end-of-life financial plans brings a lot up for people." We talked about how she might find it helpful to have a ready referral or two for a therapist, should one of her clients find that helpful. Though, we both recognized, sometimes it just means a lot to have the person you are with really listen and appreciate where you're coming from. ... we find that in most cases it takes a village – a village of care providers – to heal a person or a community after trauma or disaster. Cultivating personal and professional care networks (like the ones you can find in our Resource Guides) can help organizational leaders and staff navigate the blurrier lines that can emerge, especially when people we are with may begin to reflect on histories of trauma or adversity. Even knowing we have a colleague or trusted friend to call for personal or professional advice can bring us peace and help us feel a little more courageous in listening to others. Want to learn more about types of caregivers in a community, or read examples of how caregivers collaborate across professions to leverage greater care to survivors? You can do so in the Village of Care series.

This post, written by Rev. Dr. Kate Wiebe, originally was published on July 26, 2019, on the ICTG blog. After a crisis or disaster . . . do you "move on"? Get back to "business as usual"? "Return to normal"? Find your "new normal"? As so many of us know, all of these terms are fraught with discomfort and unease. None of them are right. All of these terms, in one way or another, can cause those of us who have survived severe loss great offense. "There's no 'moving on,'" one woman told me this week. "And," she continued, "there's nothing normal in going forward. It's just before and after. What life was like before, and what life is like after." This sentiment is especially key for organizational leaders to hear and keep in mind. How does your organization's mission take into account the large majority of people today who are living life with strong senses of "before" and "after"? How does your organization meet them where they are? Does your mission enhance life "after" what's happened? We also find that too many leaders erroneously believe that allowing members of their organization to grieve, mourn, lament, or even admit some sense of despair will cause further chaos or inhibit any movement forward. At the Institute, we find those questions are some of the most important for a leader to consider. Because your answer means the difference between being connected or disconnected with your constituents, staff, students, congregation, or community. We also find that too many leaders erroneously believe that allowing members of their organization to grieve, mourn, lament, or even admit some sense of despair will cause further chaos or inhibit any movement forward. So, instead, they strive to return to usual routines and distract their people from negative feelings by focusing everyone's attention on positive momentum. Unfortunately, complete denial of what's happened, or how it affects people, can lead some to eventual burnout, break downs, or needing to self-medicate through excessive food, substance abuse, or forms of self-harm. It's tricky, though. For many organizations, it's not appropriate to manage how their people are dealing with loss personally. By encouraging your people to embrace the local "village of care" often you will find survivors resume interest in and ability to achieve your group's mission. To navigate these common challenges, in the aftermath of loss, we encourage leaders to help their people to become mindful of what is personal or may be inhibiting their work in some way. Rather than denying these things, we encourage leaders to identify local resources where their people may turn for support as they identify personal grievances. These may include local talk therapists, art or music therapists, spiritual directors, chaplains or clergy, physical trainers or somatic therapists, physicians, friends or fellowship groups – or any combination of caregivers. By encouraging your people to embrace the local "village of care" often you will find survivors resume interest in and ability to achieve your group's mission. Sometimes, you may also find your mission expands, in light of what's happened in the larger community. How have you seen the "village of care" at work in your community? How have you seen it enhance your community's response to collective loss? Share in the comments below. You can help sustain free online education through this blog by making a small contribution today. Thank you for your generosity!

This post, written by Rev. Dr. Kate Wiebe, was originally published September 10, 2019 on the ICTG blog. When organizations – whether they are small or large businesses, nonprofits, schools, camps, or congregations – endure impacts by critical incidents within their groups, or nearby, or experience a community-wide disaster, they can encounter more dynamics than only what is experienced through individual trauma or collective trauma. To explore these dynamics further it will help to first go over a few definitions and distinctions.

So, what happens when an organization encounters a critical incident within its boundaries or a disaster within its vicinity? How can what the organization experienced be distinctive from other experiences of individual or collective trauma? In some cases, what occurs within the organization may not be that different from other examples of individual or collective trauma. The determining factor, in our experience, often is the extent to which what has occurred challenges the organization's mission. We, at the Institute, sometimes talk about collective trauma and healing in the context of how a group's spirit can break and mend. For example, when a kids' camp sees its mission as providing youth with one of the best experiences of their lives, and then a critical incident occurs in which youth become severely injured or, tragically, die, the organization's staff and leaders may experience compounding pain related both to their grief for the harm or loss of life incurred as well as the seeming assault to their mission. They may feel great feelings of guilt or remorse at having not achieved their mission in such a devastating way. In another instance, a natural disaster may cause such massive destruction that requires months or even years of rebuilding that an organization's mission may become completely thwarted in that area. This obstacle can be immensely challenging to take in and accept, let alone to adapt effectively. For second responders, including disaster responders and organizational coaches, who are walking alongside organizational leaders in these types of circumstances, it is important to be aware of the three (at least) aspects of trauma that a leader may be experiencing in a widely spread post-trauma setting: individual trauma, collective trauma, & organizational trauma. If you are interested in learning more about specific ways to support leaders impacted by critical incidents or disaster, we encourage you to explore the trainings and resource guides we offer or to reach out for a free initial consultation. You can help sustain free online education through this blog by making a small contribution today. Thank you for your generosity!

|

�

COMMUNITY BLOGFrom 2012-2021, this blog space explored expanding understanding and best practices for leadership and whole-community care.

This website serves as a historical mark of work the Institute conducted prior to 2022. This website is no longer updated. Archives

January 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed