|

This post, written by Rev. Doug Ranck, originally was published on September 3, 2019, on the ICTG blog. Another day, another shooting. Ten people killed and twenty-seven injured in Dayton, Ohio. Another twenty-two killed and twenty-four injured in El Paso, Texas. I found myself on the edge of not caring. How had it come to this? To be inoculated is the process of introducing a microorganism into one’s body, just enough to fight the potential bigger threat. Over the course of our lives, we receive countless inoculations to be pro-active in a healthier life. Given the regular occurrence of shootings in our nation and world I had to consider I may have been “inoculated” to the point of accepting shootings as a more standard part of life and not feeling the horror and sadness as I once felt. This realization shook me. It was anything but pro-active in making my life healthier. My understanding of the inoculation effect became magnified in mid-July of 2019. In my role as youth minister of a local church, I chose to take some select high school students to our denomination’s once-every-four year national/international leadership conference. For four days they experienced leadership at work on the national stage. We observed different processes of electing leadership, the debate of theological and social justice issues and ratification of new policies to be introduced in the polity of our denomination. In addition, we spent time interviewing various leaders from around the nation and the world to gain a better perspective on what it means to be a leader. ... I had to consider I may have been “inoculated” to the point of accepting shootings as a more standard part of life and not feeling the horror and sadness as I once felt. This realization shook me. It was anything but pro-active in making my life healthier. Most of these interviews were planned in advance but one day I was led by a third party to a table in the middle of the exhibition hall where seated were Bishop Lubunga and his wife, Esther of The Democratic Republic of the Congo, who cares for over 500 churches there. Having known a little about the unrest and danger of this country I found myself frozen in where to begin the interview. Out of respect for him, we stuck to very general questions and let he and his wife talk about their leadership role. In their statements, we heard some of the challenges they faced. Fast forward four weeks and I received an email from our denomination calling for special prayer focusing on our brothers and sisters in the Congo. The ongoing civil war was escalating with waves of tribal conflicts, armed groups causing havoc in villages, houses being burned, animals slaughtered and people being killed. The U.N. refugee agency reported that 4.5 million are displaced inside the Congo. Ebola and cholera are spreading since the U.N. and Doctors Without Borders are unable to operate at full strength. I had not understood the depth of trauma our bishop and his wife were experiencing - personally, and vicariously as they care for their people. My heart was broken as our congregation came together in the morning worship services to lament and pray for peace and deliverance. As I led the prayer I found myself physically shaking and my heart was racing. These leaders understood the value of being ready not for “if” but “when.” They were not comfortable settling for a world swirling with trauma. I felt the weight and pain of this beautiful country and yet I was no longer feeling it for my own. How true might this be for many more people in the U.S. who have grown “accustomed” to shooting deaths and fear in our public places? A few weeks ago, I was invited to Pendleton, Oregon for the purpose of training faith-leaders on how to shepherd trauma-informed ministries. Whenever I am in the presence of other leaders who desire to be pro-active in trauma work, I am inspired. There is often little to no motivation until an event occurs. These leaders understood the value of being ready not for “if” but “when.” They were not comfortable settling for a world swirling with trauma. How do we move from inoculation and apathy to lament, compassion, and action? In our ICTG Resource Guides, we propose calming, connecting and communicating as core ingredients for healthy trauma response. I would like to also propose those, with a few details, on how we make the much-needed move: CALM

CONNECT

COMMUNICATE

Do you have an ICTG Resource Guide? Each is an in-depth training manual for trauma preparedness and response. They include restorative strategies to expand care, build resilient groups, and provide safety for traumatized people to heal and thrive. Faith Leaders:

Community Leaders:

2 Comments

This post, written by Kate Wiebe, originally was published on May 23, 2017, on the ICTG Blog. At 2:30pm, beginning descent into Los Angeles International Airport, my fellow passengers from London, England, and I were gathering our personal items and ensuring our tray tables were up and our seats were in full upright positions. Of course, none of us imagined the terror occurring in Manchester at that same time. The first news I received, about 45min later, was when a colleagues simply posted "Manchester" on her Facebook feed. An ordinarily thoughtful and articulate woman, this one word signaled the truth: What words suffice in the aftermath of horror and devastation? The fact that this latest terror attack targeting children and teenagers at the height of leisure and celebration only proves all the more gut-wrenching for people near and far. Some of my own experience of disorientation came as I took in the fact this occurred as I was returning from a trip to England where fellow seminary professors and I studied and prepared to teach ordinands trauma-informed ministry in response to collective traumas. How painful to have to put into action so immediately some of the practices we diligently prepared only hours before. Here you will find guides for pastoral response to local collective trauma, particularly involving children and teenagers, including basic principle and tips that have proved helpful in other communities stricken by terror. In the coming weeks, local clergy and ministers may also find the Phases of Collective Trauma Response a helpful conversation piece as they discern next steps together. You can also share best practices with one another in the comments below. Prayers continue for everyone impacted and responding to the bombing in Manchester, England. And much gratitude for all the family, friends, colleagues, and first responders offering much needed help and support in yet another time of great need. This post originally was published on the ICTG blog. Prayer of Lament, with verses from the Psalms including Psalm 19 & 74 God of the cross and the lynching tree, of the jail cell and the street corner, of the bible study and the police car, look upon the world you have made. See how it is full of hatred and how violence inhabits the earth. Gunshots ring out under the heavens that declare your glory, singing the destruction of your children. Do you not hear our songs? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The streets and sidewalks of your dwelling place flow with blood, pouring out the cries of your beloveds. Do you not hear our cries? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The breaths snatched from lungs swirls on wind that blew creation to life, echoing with the last gasps of your dear ones. Do you not hear our gasps? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The bones that you knit together in a mother's womb are broken, rattling with the earth-shaking suffering of your people. Do you not hear our rattling? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The clanging of cell doors resounds amidst the music of the spheres, tolling the lives stolen by systemic oppression and unspeakable violence. Do you not hear the tolling? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The crashing of fire-licked windows mingles with the praise and prayers of generations, shattering the refuge and safety of your sanctuaries. Do you not hear the shattering? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? In these days, as in days past, our mothers and grandmothers have become mourners, our fathers and grandfathers have become grievers, our children have become wanderers in vacant rooms, our kinfolk have become pallbearers, our communities have become filled with empty chairs. Remember the people you have redeemed, Holy One. Remember the work of salvation brought about by your love. You made a way out of no way for slaves to cross the sea on dry land. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us the cries of outrage. You made water to flow in the desert for Hagar and Ishmael when they were driven out. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us commitment to the long struggle for justice. You cast out demons so that people might be restored to community. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us the determination to drive out racism. You witnessed the death fo your Beloved Child. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us the grief that cannot be comforted. You brought new life from the crucifixion of state violence and the wounds of abandonment. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us courage to speak truth to power, and hope to hatred. God of the ones with hands up and the ones who can't breathe, of those who #sayhername and those who #shutitdown, of "we who believe in freedom" and we who "have nothing to lose but our chains," look upon the world you have made, Do no forget your afflicted people forever so that we might prayer your holy name with joyful lips. Amen. Rev. Traci Blackmon, Executive Minister of Justice and Witness Ministries of the United Church of Christ, Senior Pastor of Christ the King United Church of Christ in Florissant, MO, and a leading pastoral advocate in Charlottesville, VA, recommends the following Prayer of Lament for worship services today and in the coming weeks. The prayer is written by Rev. Dr. Sharon R. Fennema, Assistant Professor of Christian Worship and Director of Worship Life, Pacific School of Religion. Copyright 2015, United Church of Christ, 700 Prospect Ave, Cleveland, OH 44115-1100.

Permission granted to reproduce or adapt materials for use in services of worship or church education. All publishing rights reserved. This blog post is the final post of a three-part series from Jonathan Leonard, a doctoral student at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. The series will highlight the challenges presented by a history of racism in America, the church’s unique position to restore the broken relationship between God and humanity as a result of racism, as well as the church’s historical endorsement of the slave trade, and modern pastoral care practices that allow ministers to acknowledge, discuss, and listen to congregants in a sensitive fashion concerning this weighty issue. A new blog will be posted every month. We hope you will follow along and leave comments below. Continued from: The Image of God and Slavery in America, Part I and A Diminished Image of God in Europeans, Part II The scars of the transatlantic slave trade are present with us today. The numerous incidents of police shooting unarmed black men in the U.S. highlights the lingering legacy of the power of the sinful slave trade to damage relationships within humanity. Racial ideas formulated to justify slavery and dehumanize Africans linger and are ever present in modern day law enforcement. Early in the NFL season, controversy brewed surrounding San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kapernick’s refusal to stand for the national anthem in protest of the treatment of minorities, in particular African-Americans. The tentacles of slavery even reach out into the sphere of sports entertainment. Americans, who are woefully ignorant of much of their history, are learning more about Francis Scott Key, slave owner/white supremacist, and the author of the Star Spangled Banner. Knowledge of history is a first step. Open and honest dialogue is another step. Wynnetta Wimberley highlights America’s reticence in engaging in meaningful dialogue concerning slavery and its legacy: Today, America appears to be at an impasse, opting for trendier dialogue bent towards concern for a more ‘global’ community, rather than addressing the anguish ‘in her own backyard’. It appears more palatable, even en vogue, to rally to concern for Israeli women, Czech children, or Malaysian families than it is to broach the subject of poverty and devastation in the African American community (which finds its origins in slavocracy).[1] Euro-centered scholarship concerning the transatlantic slave trade has trended toward placing emphasis on the role of Africans selling Africans into bondage. Whites are therefore allowed not to acknowledge the extent to which they were involved in the slave trade and to take responsibility for their part in making slavery a multinational lucrative business. Wimberley writes, “Many of the contextual details of a traumatic past become lost when someone else presumes to articulate a narrative that is not one’s own.[2] It is therefore important for the ownership of the narrative of slavery be in the hands of the descendants of slaves. This is not an exclusion of European scholars from the study of the slave trade, but serves as accountability to telling the whole story while recognizing their own biases. Scholarship tends to gloss over and leaves the brutal/bestial nature of slavery in obscurity. One such book is historian Hugh Thomas’ nearly 900 page book entitled, The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440-1870. As a reader I was quite disappointed in Thomas’ approach to telling of the story of the transatlantic trade. The scholarship displayed in his book did a wonderful job of breaking down the industrial complex of the slave trade and its connections to trade and commerce. Yet he focused little if any in the nearly 900 pages on the destruction of humanity due to white supremacy. Readers would be better served to read S.E. Anderson’s The Black Holocaust for Beginners or John Henrik Clarke’s Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust: Slavery and the Rise of European Capitalism in order to get a better view of the soul crushing and immoral nature of the slave trade. John Blassingame’s The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South has the ability to give a broad scholarly view of slavery in the American south while still being able to touch on the smaller details of the sufferings, hopes, and motivations of both slaves and masters. The church has been both proponent and detractor of slavery. Theology and twisted exegesis was used to justify the slave trade along with pseudo-science and racial theory to highlight the superiority of Europeans to Africans. Pastoral care should be informed concerning the history and legacy of slavery upon the descendants of slaves. Depression and anxiety in the African-American community are strongly linked to social conditions that were created during slavery and subsequent Jim Crow years. The pastor is suited to listen to individuals in a manner that affirms their personhood (a personhood that has been attacked since arrival in America) and sees them as valued members of the community.[3] This values the image of God within the person and views their depression or anxiety as the image of God attempting to protect itself and preserve its dignity. There are several practical ways for ministers to acknowledge, discuss, and listen to congregants in a sensitive way around this issue:

Concerning people of European descent, more research in academia should be done in the fields of psychology, sociology, theology, and history concerning the psychological, social, and spiritual effects of slavery upon Europeans during slavery and their descendants. Slavery did not just affect African-Americans; it was torrid, brutal, grotesque, and intimate all in one. Centuries of establishing a racialized system built on exploitation changed Europeans and their descendants. It seems as if the surface is just being scratched upon this topic. [1]Wynnetta Wimberly, “The Culture of Stigma Surrounding Depression in the African American Family and Community.” Journal of Pastoral Theology 25:1 (2015): 20. ATLA Religion Database, EBSCOhost (12 August 2016). [2]Wimberely, 20. [3]Wimberley, 26. [4]Americans of all ages seem to fail to answer basic questions about U.S. history. A 2008 study by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, which surveyed more than 2,500 Americans, found that only half of adults in the country could name the three branches of government. The 2014 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) report found that only 18 percent of 8th graders were proficient or above in U.S. History and only 23 percent in Civics. (Saba Naseem, “How Much U.S. History Do Americans Actually Know? Less Than You Think.” Smithsonian Magazine http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-much-us-history-do-americans-actually-know-less-you-think-180955431/ (10 August 2016). Read the entire series here: The Image of God and Slavery in America, Part I A Diminished Image of God in Europeans, Part II Jonathan Leonard currently works for Safe Alliance, a 501(c)(3) based in Austin, Texas, which serves victims of domestic violence and children who are victims of neglect and abuse. Jonathan has worked in the non-profit realm with at-risk youth for nearly 10 years. He holds an M.Div and M.A. in Biblical Literature from Oral Roberts University. He is currently pursuing doctoral studies at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. He resides in the Austin area with his wife Tausha and three children, DeAnnah, Jonathan Jr., and Justin.

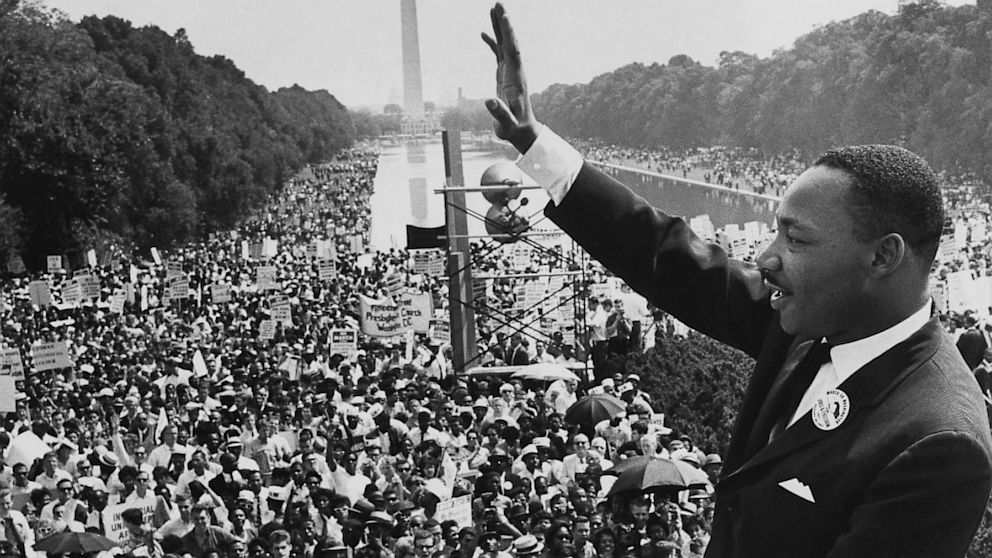

Throughout my childhood I had a vivid imagination and dream life. Like most kids, I developed the ability to have rich dreams that became increasingly complex. Thankfully, as these dreams increased in their complexity, rarely did they result in nightmares or night terrors. It wasn’t until my late teens that I realized how my subconscious mind through my dreams would solve problems I was presently faced with. If I were wrestling with a decision, it seemed that through an intense dream I’d receive the clarity I needed to make a choice. As a result, I’ve found that when faced with a personal or professional challenge — after sorting through the facts — more often than not, if I give my body and mind permission to rest, the solution will rise to my conscious mind. But, two years ago I stopped dreaming. Actually, I stopped recalling my dreams. Gone were the brilliant colors and picturesque scenes. Instead, I’d awake from hazy images of gray that I could not comprehend. My wild dreams that once served as a welcomed respite were no longer accessible. Psychologists note that dreams may be repressed due to trauma, stress, or anxiety. And, it seems the sudden loss of my father was the trauma that resulted in my inability to recall my dreams. My bold imagination had shifted dramatically. In truth, trauma may impact our psyche to the extent we experience heightened anxiety, increased irritability, lethargy, or emotional detachment. It can result in weight loss or gain or an increased vulnerability to fear. Trauma is real and its impacts cannot be underestimated. Then, we are challenged to consider how we promote national healing, racial reconciliation, and congregational health in trauma-filled communities. Trauma-filled communities — a designation slowly gaining credence among trauma experts — are communities categorized as having high crime rates and a lack of resources. As a result of deindustrialization, high local unemployment and political disenfranchisement, the landscape decays making life appear lackluster. The sight of trash-scattered sidewalks and abandoned buildings clouds the senses to the possibilities alive around residents. Indeed, dreams may be deferred because of personal, professional, or communal trauma. However, the biblical account of the character Joseph provides comfort for those who have lost the ability to dream or recall their dreams due to trauma. In the story, God dreams a dream in the young man living within a context that is not conducive for dream growth. He’s favored by his father and hated by his brothers. Tested in a context with an uneasy admixture of love and hate, he’s affirmed by the one from whom he came but rejected by his kin. Joseph is favored and hated. But, what God dreams through the favored-hated one is reason enough for us to celebrate. In his dream life he sees himself in a better state of being in comparison to his brothers and parents. Sadly, disgusted and intimidated by the possibility of the reality of his dream, his brothers hate and conspire against him as his father deflates his dreams of grandeur. That God would dream not one, but two dreams in a community that is unable to steward dream development is puzzling to me. Even more, that God would reveal divine plans in a climate where love and hate coexist, admittedly, causes me to question God’s methodologies. What is it about the soil of love and hate that serve as good ground for dream planting? With that, why would vivid imaginations and complex dreams arise within the company of dream snatchers? I contend dream snatchers are people who seek to undervalue the dreams of another person because of their own feelings of insecurity and fear. They are those who dismiss and crush God’s dream through someone else. Indeed, Joseph's family members were dream snatchers. The iconic “I Have a Dream Speech” delivered at the Lincoln Memorial by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., is both poetic and prophetic. Speaking poignantly to the injustices of his day, he grappled with the reality of the Emancipation Proclamation and the contradicting reality of the continued captivity of African-Americans as a result of segregation and discrimination. While the Declaration of Independence guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and pursuit of happiness, it seemed this was only extended to people were not of the African diaspora. It was in the soil of love and hate that God dreamed this dream in Rev. Dr. King Jr.. In other words, while the white majority loved how black mothers and grandmothers cared for their children, cleaned their homes, cooked their meal, and washed their clothes — they nonetheless hated their black skin. The soul in their voice and rhythm in their hips was welcomed entertainment, but the rich texture of black hair and resilience in their eyes was something to tame. Because the soil is still fertile with love and hate, oppression and injustice, God still dreams. Though we live in a present nightmare where George Zimmerman was acquitted in the murder of Trayvon Martin, and there were non-indictments in the deaths of Eric Garner and Tamir Rice, we continue to believe the dream God is dreaming in us. The nightmare began when our ancestors were stripped of their African garments, loaded on ships and packaged like sardines. The nightmare continued as those who survived the voyage across the Atlantic were sold as beasts on auction blocks. White supremacist ideologies want us to forget the atrocities of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. They want us to forget that we are haunted by the ghosts of cotton fields, slave quarters and lynchings. Sadly, this was no dream. Antagonists want us to forget those who were whipped, amputated, boiled in oil, separated and sold across the country. It’s prevailing principalities and powers that tell us to get over these injustices and atrocities. Get over Trayvon Martin, Sean Bell, Amadu Diallo, Mike Brown, and Sandra Bell, they contend. No! We can’t just get over these or any other lives stripped from our communities. For, these lives are buried in the soil of love and hate that give rise to our dreams of equality. Just like Joseph’s brothers who became intimidated by his dream, so has America become fearful of our rallying cry that, “Black Lives Matter.” Met with the rebuttal that all lives matter we’ve had to contend with modern day dream snatchers. As an African-American community we’ve had to steady ourselves in the face of well-intentioned but ignorant people. Yes, all lives do matter, and are created in the image and likeness of God. All lives matter — black, white, Hispanic, and Haitian, married, single, divorced, separated, heterosexual and homosexual, republican and democratic lives all matter. Nonetheless, when we cry “Black Lives Matter” it's not to subjugate any other race, but a reminder to oppressive systems that even if they don’t recognize God’s glory upon us, we do. It's a reminder to the world that we’re fearfully and wonderfully made. As Dr. King shared in this letter from the Birmingham jail, “There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair.” The rallying cry that black lives matter indicates the cup of our endurance has run over and God is dreaming a dream thru Millennials for this present age. The God given dream through Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is the same dream given to the world today. He or she who has an ear, let them hear what the spirit is saying. For the spirit speaks and dreams of a prison system that does more to rehabilitate inmates than use inmates as cheap labor. The spirit dreams through us of the deconstruction of institutionally oppressive systems that promote social, economic, housing and environmental inequities. As Rev. King said, “It is a historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntary give up their unjust posture; but as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.” Therefore, those living and working in the legacy and spirit of Rev. King must continue to dream and advocate for rights actions and outcomes concerning all citizens. This is the dream God continues to dream through us. Dawrell Rich is an author, pastor and public speaker. He is also the founder of Joshua’s House - a youth and young adult leadership organization that focuses on mentoring, community service, health & wellness and education. He has earned a reputation as a compassionate pastor, catalyst for change, and dynamic communicator.

For more information: www.dawrellrich.com Twitter: @dawrellrich FB: dawrellgrich This blog post is the first in a three part series from Jonathan Leonard, a doctoral student at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. The series will highlight the challenges presented by a history of racism in America, the church’s unique position to restore the broken relationship between God and humanity as a result of racism, as well as the church’s historical endorsement of the slave trade, and modern pastoral care practices that allow ministers to acknowledge, discuss, and listen to congregants in a sensitive fashion concerning this weighty issue. A new blog will be posted every month. We hope you will follow along and leave comments below. The image of God within people of African descent has been marred and consistently challenged from the beginning of the American experiment. This has been quite evident throughout the nation’s history. Yet the racism practiced in U.S. history can be seen as a manifestation of humanity’s fall in Genesis 3. In Genesis 1 and 2 God establishes order and proper relationship between Deity and creation and healthy relationships within the created order. Genesis 1:26-27 teaches that God created humanity in His/Her image and likeness. This endowed humanity with an innate dignity and a value. Every human regardless of gender, age, skin complexion, or physical ability is valuable. God gave humanity dominion over the animals of the earth, yet did not give humanity dominion over other humans. The desire to dominate fellow human beings came when humanity chose to move from a position of relationship with God to exultation and centering upon self. This was a veritable Pandora’s Box where sin in many forms manifested. Racism is one such sin that has particularly plagued humanity within recent centuries. Slavery throughout the millennia has had the pernicious characteristics of greed, brutality, and exploitation. The great Greek philosopher Aristotle stated this while questioning the humanity of slaves: For a man who is able to belong to another person is by nature a slave (for that is why he belongs to someone else), as is a man who participates in reason only so far as to realize that it exists, but not so far as to have it himself…other animals do not recognize reason, but follow their passions. The way we use slaves isn’t very different; assistance regarding the necessities of life is provided by both groups , by slaves and domestic animals. Nature must have intended to make the bodies of free men and of slaves different also; slaves’ bodies strong for the services they have to do, those of free men upright and not much use for that kind of work, but instead useful for community life.[1] Aristotle’s animalization of slaves is clearly dehumanizing. It seems to render them as tools, or rather some sort of animated tools. The same way a saw is the extension of its user, so the slave was an animated tool and extension of their master’s will. While slavery in the ancient world was clearly exploitative, it was also strangely egalitarian in that nearly anyone could become a slave in that world. An aristocrat whose city was conquered or an enemy combatant captured on the battlefield could easily become the property of their conquerors. Pirates swarmed the seas and routinely preyed upon ships, islands, and coastlines enslaving people in raids. In the Greco-Roman world, many nationalities and races were represented in the slave markets of the empire. Yet it was during the transatlantic slave trade that slavery would gain a racial component.[1] This would be the first time in Western history where a specific racial group of people became universally tied to perpetual bondage. David Brion Davis writes, “As slavery in the Western world became more and more restricted to Africans, the arbitrarily define black “race” took on all the qualities, in the eyes of many white people, of the infantilized and animalized slave.”[2] The Avalanche The challenge to the image of God in people of African descent in America continues this day and can be witnessed in the various forms of police brutality. In June of 2015 in Austin, Texas, a police dashcam captured a white Austin police officer slamming a slender African-American woman to the ground. The woman’s name was Breaion King, a twenty-six year old elementary school teacher. She was pulled over for speeding, but things quickly escalated which led to her being slammed to the ground and handcuffed in the back of a squad car. Yet it was King’s interaction with another officer in the vehicle that seemed to raise eyebrows even further. King questioned the officer: “Why are you all afraid of black people?” The officer then replied to King’s question stating blacks have “violent tendencies” and “intimidating” appearance. He went on further to state: “Ninety-nine percent of the time … it is the black community that is being violent,” the officer told her. “That’s why a lot of white people are afraid. And I don’t blame them.”[3] These comments started an avalanche in my mind concerning racism, American history, the image of God, and the role of religion in justification of slavery. These comments from the officer are a manifestation of generations of thought formulated in the realms of politics, economics, law, science, and religion. Many Americans are woefully ignorant of the basics of U.S. history such as naming the victorious side in the Civil War, who the U.S. gained independence from, or naming the vice-president.[4] This presents a greater challenge to understanding the historical underpinnings of white supremacist thought and how it undermines the ideals espoused by the country’s founders. How does this link to understanding the image of God and slavery? In the encounter between King and the officer, was the image of God exulted or diminished? (When I refer to the image of God, it is in reference to the image of God in Breaion King and the officer who slammed her as well as the officer who made those comments about African-Americans). Continued...This blog post is the first in a three part series. Read the entire series here: A Diminished Image of God in Europeans, Part II The Image of God and Slavery in America, Part III [1] For more elaboration on the shift from slavery being a status that nearly anyone had the possibility of falling into to the racial component later imposed by Western nations on Africans see David Brion Davis, In the Image of God: Religion, Moral Values, and Our Heritage of Slavery. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. See also Milton Meltzer’s work, Slavery: A World History. Chicago: Da Capo Press, 1993. [2] Davis, 128. [3] Michael E. Miller, “Austin police body-slam black teacher, tell her blacks have ‘violent tendencies,” (22 July 2016) https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/07/22/video-austin-police-body-slam-black-teacher-tell-her-blacks-have-violent-tendencies/ (10 August 2016) [4] Americans of all ages seem to fail to answer basic questions about U.S. history. A 2008 study by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, which surveyed more than 2,500 Americans, found that only half of adults in the country could name the three branches of government. The 2014 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) report found that only 18 percent of 8th graders were proficient or above in U.S. History and only 23 percent in Civics. (Saba Naseem, “How Much U.S. History Do Americans Actually Know? Less Than You Think.” Smithsonian Magazine http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-much-us-history-do-americans-actually-know-less-you-think-180955431/ (10 August 2016). Jonathan Leonard currently works for Safe Alliance, a 501(c)(3) based in Austin, Texas, which serves victims of domestic violence and children who are victims of neglect and abuse. Jonathan has worked in the non-profit realm with at-risk youth for nearly 10 years. He holds an M.Div and M.A. in Biblical Literature from Oral Roberts University. He is currently pursuing doctoral studies at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. He resides in the Austin area with his wife Tausha and three children, DeAnnah, Jonathan Jr., and Justin.

The notifications came like a tsunami to my cell phone: “Active shooter situation in San Bernardino” “Unknown number wounded and killed.” My first reaction: “Not again. I’m weary of this, I’m discouraged. How long will it be until this happens in my neighborhood . . . again?” Perhaps you experienced those feelings too. I had to stop and wonder why I think so many other countries are dangerous to visit when my own is impacted weekly by active shooters in schools, churches, universities, malls and community centers. Sadly, it has become a new normal.  This weekend, in the context of the church, I will be debriefing with our gathered youth the events of the last week. In former days this would have happened rarely and only following an event I subjectively measured as “big.” Or, it might have happened if one of our youth brought it up as a prayer request or if the national news was covering it for consecutive days. It might have been perceived as an “option” but not likely a necessity. I propose we are in a season where debriefing is now a necessity. With the frequency of terrorist acts and mass shootings now a regular occurrence – more than five have happened in the last two weeks alone – and how social media creates incessant communication, it is important for us as youth leaders to recognize that the trauma of these many episodes no longer lies below the surface for our youth and children. The smiles on the faces of our youth may be hiding anxiety they are feeling. And it is important for us, as leaders, to be honest with our youth in age appropriate ways when we are the ones feeling anxious. Join me this Sunday or the next time you meet with your youth to reflect and talk as a “family.” Here is a simple game plan you could adapt in your debrief time to fit your own context:

Make this plan your own. What other ideas would you add? What's worked well for your groups in the past? Doug Ranck is associate pastor of youth and worship at Free Methodist Church of Santa Barbara, CA. With three decades of youth ministry experience, he serves as ICTG Program Director for Youth Ministry, as well as a leading consultant, trainer and speaker with Ministry Architects, the Southern California Conference, and, nationally, with the Free Methodist Church. He has written numerous articles for youth ministry magazines and websites, and published the Creative Bible Lessons Series: Job (Zondervan, 2008). Doug is happily married to Nancy, proud father of Kelly, Landon and Elise, and never gets tired of looking at the Pacific ocean every day.

I did not want to write this.

Not again. I did not want to have to write one more response, reflection, or blog post about the process of a campus healing after a shooting, not one more word. But here I am three weeks after the Umpqua Community College shooting in my beloved state of Oregon, still trying to comprehend the tragedy, loss, and deep grief that yet another campus shooting has left behind. Yuck. In blog posts past I have offered many thoughtful and thought out tips and suggestions for those supporting college students in the wake of a campus shooting. Some of these suggestions have included holding a time for prayer and reflection, creating space for grief and processing, and acknowledging the need for lament in it’s many forms. These are good suggestions and I certainly would like to highlight them again as great tips in helping campus communities work through their loss… however right now I want to suggest something different – action. After Sandy Hook it was a no-brainer – something needed to be done. As has happened many times throughout our recent history, celebrities came together to make a statement – in a simple black and white video – to say three words: Enough is enough. The message was simple – enough is enough. We need to change what has been broken, do something – anything. No more names, no more lists of names, no more schools. No more. With that cue, I suggest here additional ways we can support our campus communities in light of local or national massive campus tragedy and loss. Call the Question When a massive tragedy like a campus shooting happens many questions come to the surface. Some of these questions are rhetorical, others honestly seek understanding and answers. Be intentional and create space for the questions – both big and little, both personal and communal, both isolated and mobile. Many of us process our experience in words. Creating space for key questions not only offers students the chance to reflect, but starts to get at important concerns. This process of calling the questions can be done as an event, small group activity, restorative justice peace circle, or over a meal. Have a moderator or host begin and then let the questions come. Where was God in this moment? What is the role of grace and forgiveness in this moment? Where is God’s goodness/ fairness/justice in this moment? If God is good then why….? Why did this happen? Then, host a discussion around them. Where do the questions come from? What are their roots? How might we go about answering them in community? Remind the group gathered that the questions don’t need to be answered today. They do need to be asked and to be heard. Asking questions has theological implications and challenges students to see what is symbolic in the experience, deepening their engagement with pressing issues. Get Angry Get angry about this. It’s ok to get angry, and it’s ok for students to work through their anger as well. When anger surfaces after massive trauma, we as leaders can model our freedom to let it come and reflect on the why and how it is. Walking students and communities through this emotion is crucial. As mentioned above, key questions are tangible means of engagement and can assist students into deeper reflection in relation to the anger they feel in the aftermath of mass violence. Invite students to consider: What exactly are you angry about? Where do you think it is coming from? What will you do with this emotion? Identifying answers to these questions can help students begin to feel more focused and grounded, and less chaotic following the disparate experience of initial shock. After Sandy Hook I was angry. We had just had our first child and during those early weeks of his life I rocked him in his nursery as my husband watched the news in the room down the hall. I could hear the names being read of the children that died in that campus shooting -children. I was angry because of the injustice and the pain. I was angry because I was so happy about being a new mother with a beautiful child and I could not bear to think of the pain of losing my own child if that had happened to our family. I grieved deeply for the mothers who lost their babies. It was infuriating. Reflecting on this emotion taught me so much about myself, what I cared about, and how much certain issues meant to me. By reflecting on my anger, I was thrown into the depths of prayer and lament to God. There my understanding of God and God’s love, compassion, and grace grew. It was an incredible learning and stretching experience for me. I know it is an experience our students can learn from as well. Finally, the best thing about anger is that it can get us going and motivate us to action. Perhaps your action may be entering into a deeper experience of prayer or outpouring to God. Perhaps your action may involve deeper engagement with community instead of becoming isolated. There is solidarity in this form of lament. Or, perhaps, your further action moves you toward acts of justice, awareness, healthy living, and correcting. When guided in positive ways, anger has great potential to lead us to big action which can bring about important change. Do Something – Anything Finally, nothing will change if we don’t do something. Caring about issues like campus violence – whether the issues are racial or gender specific micro-aggressions, campus shootings, dating violence, or sexual assault – is only half the battle. We must accompany our care and concern with action. We must let our good intentions manifest into change. Or else, truly nothing will happen. On a pragmatic scale this might look like starting a letter writing campaign with students. It might mean attending or organizing a community conversation on these issues. It may mean participating in a protest, sit in, or march. Or, like the Enough is Enough video – it may involve using the arts to communicate the importance of an issue or topic. Gather for memorials and prayer services. Gather for call to action events and get your local communities involved so those around you and your community understand that you are not willing to take it anymore. As we say in the national sexual assault bystander program Green Dot – We don’t need to do everything, but we can do something. My hope after Sandy Hook was that this anger, this nationwide anger, would lead to change – after all, what was it going to take if not this horrific tragedy? But here we are three weeks later from another campus shooting. And, sadly, more incidents have occurred since then. We are not alone, we are together. We are community and we can make a difference. Change can happen. Enough is enough.

Director of Social Concerns Seminars in the Center for Social Concerns (University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana), Melissa is a social entrepreneur, a feminist liberation theologian, and a trained community organizer. She works with university students in academic and experiential environments to respond actively to most pressing social concerns of our time. She lives with her family in South Bend, Indiana.

ICTG welcomes guest blogger, Rev. Shaun Lee, pastor of Mount Lebanon Baptist Church, Brooklyn, NY, sharing about congregational responses to the 2014 Eric Garner killing in New York City. Thousands of people around the globe filled city streets with banners and signs chanting "I can't breathe" in response to a grand jury's decision to not indict New York City police officer Daniel Pantaleo for the killing of Staten Island resident Eric Garner. It was a decision that was highly anticipated given the backlash for a lack of indictment of another policer officer in Ferguson, Missouri for the killing of a young unarmed black male named Michael Brown. New York City especially felt the effects of this decision with protesters walking the streets for several successive evenings in an effort to disrupt traffic and city logistics with an understanding that if the citizens could not get justice, then the city would not get peace. Police presence was heavy, but they were given instructions to allow peaceful protests to go unobstructed. The mayor's empathetic tone for protestors put police officers on edge. During this turmoil another police officer shoots an unarmed black male named Akai Gurley as he was walking down the stairs of his building. Tensions rose throughout the city and just when things were reaching its peak two NYPD officers were shot while sitting in their patrol car by a man who claimed to be exacting revenge for the recent victims of police killings. All of this happens within a span of 17 days and the question is how does the church engage in the healing process when so much community trauma has taken place. My congregation, and several others have chosen to engage in protest, prayer, and partnership as a way of promoting healing and peace within our congregations and community. After the decision of the grand jury to not indict officer Pantaleo several Brooklyn pastors joined together in an effort to create a space for the church to practice peaceful protest for those who could not and would not join in the late night protest. This was a particularly sensitive issue because several members of the congregation are police officers, but in dialogue with them and other officers I felt confident in promoting this protest without the fear of it seeming anti-police. We ended service early and marched with several other congregations within the community to express our discontent and to stand in line with the rich history of the African American church of speaking up to issues of injustice. As we marched onlookers within the community joined our walk, sang beside us, and prayed with us. Since prayer is a tool for transformative power the march ended with a prayer rally. Congregations had been praying on their own, but it was important to pray together as a part of the larger community. It was a great moment for the community and a call to action for the churches within the community to continue experiences like this. We were called to do it again after the shootings of Officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu, the two officers shot in their patrol car. The shape of it changed in that it was a prayer vigil for peace and justice. We were careful to be sensitive to the police officers during their time of grief while also keeping in mind that justice was still at the forefront of the discussion. Eric Garner's sister, Ellisha Flagg, also joined us in our call for peace and spoke to all those gathered. This rally was planned in partnership with our local councilman and police precinct. Some officers from the community affairs bureau of our local precinct marched with us as we continued to try to bring healing to our community after so many devastating events began to take its toll. We prayed together for the victims of senseless violence, the safety of police officers, the relationship between the mayor and the NYPD along with the relationship between the community and NYPD. It was a sobering reminder that in the grand scheme of things all lives truly do matter and have value in the sight of God. A powerful moment occurred when one of the pastor's read the names of those who were killed in our community to violence in the past year. As each name was read and single white ballon was released into the sky. Certainly the need for continued healing is important. The local congregations have decided to continue partnering together to create experiences that foster healing and prayer. We have also decided to partner with the local police precinct and elected officials to create dialogue and ensure that the community still has a say in policy and how it is policed. Needless to say these partnerships already existed but trauma has a way of reshaping and remodeling our current practices. Through continued dialogue we are better able to deal with traumatic issues when they arise instead of being reactionary. Rally NY Dec 2014 // photos courtesy Rev. Shaun Lee Reverend Shaun J. Lee, a Brooklyn, New York native, serves as the seventh pastor of the Mount Lebanon Baptist Church. His ministry focuses on getting individuals to establish a true relationship with Christ, establishing a meaningful membership in God’s church and a concrete connection with the surrounding and global community. Reverend Lee firmly believes that the Word, Worship, and Work are central to advancing the Kingdom of God. An active member of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., Reverend Lee aims to connect with the un-churched through various pillars he’s set in place. Staying in tune with his own personal passions of social justice, he crafted institutions to reflect his ministry including a monthly soup kitchen, back-to-school BBQ that provides 500 children with supplies, a strong social media presence led by volunteers from the congregation and the Judges 19 Ministry which focuses on helping both men and women victimized by domestic abuse. Reverend Lee is married to Valerie, and delights in the nurture of their daughters Sian and Sanai.

|

�

CONGREGATIONAL BLOG

From 2012-2020, this blog space explored expanding understanding and best practices for leadership and congregational care.

This website serves as a historical mark of work the Institute conducted prior to 2022. This website is no longer updated. Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed