|

This post originally was published on the ICTG blog. Prayer of Lament, with verses from the Psalms including Psalm 19 & 74 God of the cross and the lynching tree, of the jail cell and the street corner, of the bible study and the police car, look upon the world you have made. See how it is full of hatred and how violence inhabits the earth. Gunshots ring out under the heavens that declare your glory, singing the destruction of your children. Do you not hear our songs? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The streets and sidewalks of your dwelling place flow with blood, pouring out the cries of your beloveds. Do you not hear our cries? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The breaths snatched from lungs swirls on wind that blew creation to life, echoing with the last gasps of your dear ones. Do you not hear our gasps? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The bones that you knit together in a mother's womb are broken, rattling with the earth-shaking suffering of your people. Do you not hear our rattling? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The clanging of cell doors resounds amidst the music of the spheres, tolling the lives stolen by systemic oppression and unspeakable violence. Do you not hear the tolling? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? The crashing of fire-licked windows mingles with the praise and prayers of generations, shattering the refuge and safety of your sanctuaries. Do you not hear the shattering? How long, O God, will you keep silence? How long will we fail to be your voice? In these days, as in days past, our mothers and grandmothers have become mourners, our fathers and grandfathers have become grievers, our children have become wanderers in vacant rooms, our kinfolk have become pallbearers, our communities have become filled with empty chairs. Remember the people you have redeemed, Holy One. Remember the work of salvation brought about by your love. You made a way out of no way for slaves to cross the sea on dry land. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us the cries of outrage. You made water to flow in the desert for Hagar and Ishmael when they were driven out. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us commitment to the long struggle for justice. You cast out demons so that people might be restored to community. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us the determination to drive out racism. You witnessed the death fo your Beloved Child. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us the grief that cannot be comforted. You brought new life from the crucifixion of state violence and the wounds of abandonment. Arise O God and defend your own cause. Raise up in us courage to speak truth to power, and hope to hatred. God of the ones with hands up and the ones who can't breathe, of those who #sayhername and those who #shutitdown, of "we who believe in freedom" and we who "have nothing to lose but our chains," look upon the world you have made, Do no forget your afflicted people forever so that we might prayer your holy name with joyful lips. Amen. Rev. Traci Blackmon, Executive Minister of Justice and Witness Ministries of the United Church of Christ, Senior Pastor of Christ the King United Church of Christ in Florissant, MO, and a leading pastoral advocate in Charlottesville, VA, recommends the following Prayer of Lament for worship services today and in the coming weeks. The prayer is written by Rev. Dr. Sharon R. Fennema, Assistant Professor of Christian Worship and Director of Worship Life, Pacific School of Religion. Copyright 2015, United Church of Christ, 700 Prospect Ave, Cleveland, OH 44115-1100.

Permission granted to reproduce or adapt materials for use in services of worship or church education. All publishing rights reserved.

0 Comments

This blog post is the final post of a three-part series from Jonathan Leonard, a doctoral student at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. The series will highlight the challenges presented by a history of racism in America, the church’s unique position to restore the broken relationship between God and humanity as a result of racism, as well as the church’s historical endorsement of the slave trade, and modern pastoral care practices that allow ministers to acknowledge, discuss, and listen to congregants in a sensitive fashion concerning this weighty issue. A new blog will be posted every month. We hope you will follow along and leave comments below. Continued from: The Image of God and Slavery in America, Part I and A Diminished Image of God in Europeans, Part II The scars of the transatlantic slave trade are present with us today. The numerous incidents of police shooting unarmed black men in the U.S. highlights the lingering legacy of the power of the sinful slave trade to damage relationships within humanity. Racial ideas formulated to justify slavery and dehumanize Africans linger and are ever present in modern day law enforcement. Early in the NFL season, controversy brewed surrounding San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kapernick’s refusal to stand for the national anthem in protest of the treatment of minorities, in particular African-Americans. The tentacles of slavery even reach out into the sphere of sports entertainment. Americans, who are woefully ignorant of much of their history, are learning more about Francis Scott Key, slave owner/white supremacist, and the author of the Star Spangled Banner. Knowledge of history is a first step. Open and honest dialogue is another step. Wynnetta Wimberley highlights America’s reticence in engaging in meaningful dialogue concerning slavery and its legacy: Today, America appears to be at an impasse, opting for trendier dialogue bent towards concern for a more ‘global’ community, rather than addressing the anguish ‘in her own backyard’. It appears more palatable, even en vogue, to rally to concern for Israeli women, Czech children, or Malaysian families than it is to broach the subject of poverty and devastation in the African American community (which finds its origins in slavocracy).[1] Euro-centered scholarship concerning the transatlantic slave trade has trended toward placing emphasis on the role of Africans selling Africans into bondage. Whites are therefore allowed not to acknowledge the extent to which they were involved in the slave trade and to take responsibility for their part in making slavery a multinational lucrative business. Wimberley writes, “Many of the contextual details of a traumatic past become lost when someone else presumes to articulate a narrative that is not one’s own.[2] It is therefore important for the ownership of the narrative of slavery be in the hands of the descendants of slaves. This is not an exclusion of European scholars from the study of the slave trade, but serves as accountability to telling the whole story while recognizing their own biases. Scholarship tends to gloss over and leaves the brutal/bestial nature of slavery in obscurity. One such book is historian Hugh Thomas’ nearly 900 page book entitled, The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440-1870. As a reader I was quite disappointed in Thomas’ approach to telling of the story of the transatlantic trade. The scholarship displayed in his book did a wonderful job of breaking down the industrial complex of the slave trade and its connections to trade and commerce. Yet he focused little if any in the nearly 900 pages on the destruction of humanity due to white supremacy. Readers would be better served to read S.E. Anderson’s The Black Holocaust for Beginners or John Henrik Clarke’s Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust: Slavery and the Rise of European Capitalism in order to get a better view of the soul crushing and immoral nature of the slave trade. John Blassingame’s The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South has the ability to give a broad scholarly view of slavery in the American south while still being able to touch on the smaller details of the sufferings, hopes, and motivations of both slaves and masters. The church has been both proponent and detractor of slavery. Theology and twisted exegesis was used to justify the slave trade along with pseudo-science and racial theory to highlight the superiority of Europeans to Africans. Pastoral care should be informed concerning the history and legacy of slavery upon the descendants of slaves. Depression and anxiety in the African-American community are strongly linked to social conditions that were created during slavery and subsequent Jim Crow years. The pastor is suited to listen to individuals in a manner that affirms their personhood (a personhood that has been attacked since arrival in America) and sees them as valued members of the community.[3] This values the image of God within the person and views their depression or anxiety as the image of God attempting to protect itself and preserve its dignity. There are several practical ways for ministers to acknowledge, discuss, and listen to congregants in a sensitive way around this issue:

Concerning people of European descent, more research in academia should be done in the fields of psychology, sociology, theology, and history concerning the psychological, social, and spiritual effects of slavery upon Europeans during slavery and their descendants. Slavery did not just affect African-Americans; it was torrid, brutal, grotesque, and intimate all in one. Centuries of establishing a racialized system built on exploitation changed Europeans and their descendants. It seems as if the surface is just being scratched upon this topic. [1]Wynnetta Wimberly, “The Culture of Stigma Surrounding Depression in the African American Family and Community.” Journal of Pastoral Theology 25:1 (2015): 20. ATLA Religion Database, EBSCOhost (12 August 2016). [2]Wimberely, 20. [3]Wimberley, 26. [4]Americans of all ages seem to fail to answer basic questions about U.S. history. A 2008 study by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, which surveyed more than 2,500 Americans, found that only half of adults in the country could name the three branches of government. The 2014 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) report found that only 18 percent of 8th graders were proficient or above in U.S. History and only 23 percent in Civics. (Saba Naseem, “How Much U.S. History Do Americans Actually Know? Less Than You Think.” Smithsonian Magazine http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-much-us-history-do-americans-actually-know-less-you-think-180955431/ (10 August 2016). Read the entire series here: The Image of God and Slavery in America, Part I A Diminished Image of God in Europeans, Part II Jonathan Leonard currently works for Safe Alliance, a 501(c)(3) based in Austin, Texas, which serves victims of domestic violence and children who are victims of neglect and abuse. Jonathan has worked in the non-profit realm with at-risk youth for nearly 10 years. He holds an M.Div and M.A. in Biblical Literature from Oral Roberts University. He is currently pursuing doctoral studies at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. He resides in the Austin area with his wife Tausha and three children, DeAnnah, Jonathan Jr., and Justin.

This blog post is the second post of a three-part series from Jonathan Leonard, a doctoral student at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. The series will highlight the challenges presented by a history of racism in America, the church’s unique position to restore the broken relationship between God and humanity as a result of racism, as well as the church’s historical endorsement of the slave trade, and modern pastoral care practices that allow ministers to acknowledge, discuss, and listen to congregants in a sensitive fashion concerning this weighty issue. A new blog will be posted every month. We hope you will follow along and leave comments below. Continued from The Image of God and Slavery in America, Part I. Slavery had a diminishing effect on all involved. There is much research left to be done on the damage done to people of European descent and their descendants regarding slavery. Historian Milton Meltzer writes of the detriment of slavery to both the slave and the master: For both, it is a moral disaster. It seems safe to say that a sense of one’s own worth is at the root of morality. By denying a man’s humanity, slavery prevents him from developing a sense of human dignity. As for the master, the habit of domination tends to poison every aspect of his life. For when the master’s whim controls every movement of his slave, the master’s power of self-control is weakened and destroyed. The master who recognizes no humanity in his slave loses it in himself. [1] Were all slave masters cruel? Not across the board. Slavery and the interpersonal interactions varied throughout the institution. Yet the common theme remained: the slave was viewed as lesser and inferior to their master. As Meltzer points out, this interaction poisoned the master’s life. The image of God in humans was not meant to dominate the will of others or to be dominated by the will of others. There were people who lived in the slave holding society of the American south who saw the monstrosity of the system. One such person was Mary Chestnut. Chestnut was a part of the wealthy landed planter class of the south and viewed the behavior of fellow whites with disgust while writing in her journal: God forgive us, but ours is a monstrous system & wrong & iniquity. Perhaps the rest of the world is as bad. This is only what I see: like the patriarchs of old, our men live all in one house with their wives & their concubines, & the Mulattos one sees in every family exactly resemble the white children & every lady tells you who is the father of all the Mulatto children in everybody's household, but those in her own, she seems to think drop from the clouds or pretends so to think.[2] Could Mary Chestnut’s reaction to her society be the image of God within her revolting at the injustices around her? Mary Chestnut was a member of a family that profited greatly from their ownership of slaves and the production of unpaid labor. She inherited the racist attitudes of her society, yet the image of God is reacting with disdain at the state of affairs. The diminishment of the image of God in European Americans can be seen at the inception of the U.S. and its declaration of independence from British rule. America was founded on the premise of freedom, equality, and the right of all men to pursue their destiny. Yet it was also founded in an era where slavery was common. The founding fathers, many of them slave owners themselves, were not idiotic men. They were keenly aware of the contradiction that this represented. Thomas Jefferson, the architect of one the greatest documents of freedom, the Declaration of Independence could be seen as attempting to grapple with the evil of the transatlantic slave trade in this clause that was omitted from the final draft of the declaration (Jefferson is referring to the king of Great Britain): He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the person of a distant people who never offended him; captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain.[3] Jefferson, a slaveholder himself, was forced to omit this clause from the Declaration in order to appease the slaveholding colonies. Could this clause be a manifestation of the image of God in Thomas Jefferson? Thomas Jefferson was a benefactor of the slave system and held white supremacist views.[4] Yet he was also keenly aware of the injustices inherent in the institution of slavery. People like Thomas Jefferson and Mary Chestnut saw the hypocrisy and evil inherent in the institution of slavery. Yet they were themselves benefactors of that same pernicious institution. What could they do but look around at the state of the society they lived in and feel powerless to change it? Meltzer recalls an account of a Northerner visiting the South for the first time. He passed through many southern cities and observed a fortress-like society: “You come to police machinery such as you never find in towns under free government: citadels, sentries, passports, grape-shotted cannon, and daily public whippings.”[5] Southern whites had to go to great lengths to repress the slaves in their society. The image of God in the slaves manifested itself in revolt to bondage through acts of sabotage, running away, poisoning, suicide, and rebellion to name a few. Historian John Blassingame records 55 mutinies on slave ships from 1699 to 1845 as well as passing references to over one hundred other mutinies[6]. The image of God in whites was diminished as their will and efforts were considerably expended on the management and repression of an entire race of people. What about the defenders of slavery in the American south? Where they all inherently evil? It would be easy to lump all of the men who defended slavery as evil. There were many arguments formulated by defenders of slavery pulling from diverse disciplines in order to justify their practices. If these people were so evil, why would they go to such great lengths to formulate arguments to justify their institution of slavery? A Theological Response The burden of the history concerning the transatlantic trade is weighty indeed. Study of this massive historical injustice hits on so many levels. As an African-American descendant of slaves, I read about the conditions my ancestors most likely endured and think about how I would have reacted in such a situation. I look at my children and think about my great-great grandfather Gray Sr. who was put on the auctioning block in North Carolina in 1830 along with his five brothers, and was sold away from them to Louisiana, never to see his brothers again. I look at my wife and think, how would I feel if the slave master who had the right, could take my wife from our bed and take her to the bed of a visiting friend for the night. Studying this topic has been infuriating, traumatizing at times, and exhilarating all at once. It’s as if I am studying the history of crimes committed in broad daylight without any redress. Yet the resilience of the Africans under such circumstances is inspiring. Delroy Hall formulates the idea of re-imagining the Middle Passage as an existential crucifixion. In his article, he links the suffering of African slaves to the suffering and crucifixion of Christ using Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and Resurrection Sunday as models for the African experience in the Middle Passage.[7] What Jesus experienced on Good Friday is paralleled to the experiences of Africans. Jesus endured the humiliation of being stripped of clothing, mocked, flogged, and publicly crucified. Hall links the suffering of Africans to Good Friday. In Christianity, the focus is usually placed upon Good Friday and a fast forward to Resurrection Sunday. Silence seems to fall in the middle of Holy Saturday. Holy Saturday is the place of the grave. It represents mourning and a dark night of the soul. Jesus was in the grave. Hall calls the cargo hold of the slave ships tombs for Africans. These makeshift coffins where places for existentially dead people.[8] Yet just as Holy Saturday was not the end for Jesus, so the Middle Passage was not the end for the Africans involved. Jesus prophesied his death and resurrection. Hall highlights four aspects of Resurrection Sunday for the enslaved: forming relationships, maintaining their original languages and developing new ones, mutinies, and suicide.[9] These were actions of protest that against their enslavement and it was an assertion of their humanity, constant expression of the image of God.[10] The resurrection of Christ is central to Christianity. Jesus rose but carried the scars of Good Friday which were a testament to his suffering. The present day descendants of enslaved Africans of the Diaspora in the New World are survivors who may not have been enslaved but still carry the scars of slavery, Jim Crow, or colonialism. Reparations The church is in a unique position to play a significant role in this process. While the church was duplicitous in the continuation of the slave trade, it also was instrumental in its demise. The Quaker movement in North America would become the early leaders in the abolitionist movement. Strong Christian leaders such as William Wilberforce inspired by the effects of the Second Great Awakening would lead the charge to abolition. Ministers such as John Wesley, Charles Spurgeon, and Charles Finney spoke out against the evils of slavery. Women such as Harriet Beecher Stowe and Sojourner Truth utilized the spoken word and the pen to motivate others to see the injustice of slavery. At the heart of Christian theology is reconciliation, reconciliation of a broken relationship between God and humanity. As the relationship between God and humanity is restored, so it is with the relationship between members of the human family with one another. Thus far in the U.S. reparations have not been offered. Affirmative Action, a modest form of reparation, used as a redress for slavery have been met with routine opposition. Roy L. Brooks in his book Atonement and Forgiveness: A Model for Black Reparations, offers a model for meaningful reparations: 1) Apology/Atonement 2) Reparation 3) Change in behavior.[11] Brooks writes, “When the government makes a tender of apology, it is attempting to reclaim its humanity, its moral character, its place in the community of civilized nations in the aftermath of the commission of an unspeakable human injustice.”[12] Implementation of these steps can be facilitated by the government. This can be achieved utilizing the legislative process, yet it should not be forced or coerced. The power of asking for forgiveness from those wronged is a powerful act which could cleanse the perpetrators or their descendants from the taint of the atrocity. Yet before the church gets heavily involved in the reparations/atonement process, it must come to grips with its own role in its endorsement of the slave trade. Horrible exegesis and conformity to the status quo helped to secure the business of slavery in America. Continued...This blog post is the second post of a three part series. Read the entire series here: The Image of God and Slavery in America, Part I The Image of God and Slavery in America, Part III [1] Meltzer, 4. [2] Mary Boykin Chesnut, Mary Chestnuts Civil War. Edited by C. Vann Woodward. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 29. [3] Darlene Clark Hine, William C. Hine, and Stanley Harrold, The African-American Odyssey. (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2000), 595. [4] Jefferson would go on to pen Notes on the State of Virginia in which he explicitly expressed his views of the inferiority of blacks to whites utilizing the disciplines of history, science, political theory, and racial theory. (Finkleman, 20). [5] Meltzer, 209 [6] John Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (Oxford University Press, 1979), 11. [7] Delroy Hall, “The Middle Passage as Existential Crucifixion.” Black Theology: An International Journal 7 (2009):51. ATLA Religion Database, EBSCOhost (13 August 2016). [8] Hall, 51. [9] Hall, 54. [10] Hall, 54. [11] Roy L. Brooks, Atonement and Forgiveness: A Model for Black Reparations (Berkley: University of California Press, 2004), 144. [12] Brooks 144-145. Jonathan Leonard currently works for Safe Alliance, a 501(c)(3) based in Austin, Texas, which serves victims of domestic violence and children who are victims of neglect and abuse. Jonathan has worked in the non-profit realm with at-risk youth for nearly 10 years. He holds an M.Div and M.A. in Biblical Literature from Oral Roberts University. He is currently pursuing doctoral studies at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. He resides in the Austin area with his wife Tausha and three children, DeAnnah, Jonathan Jr., and Justin.

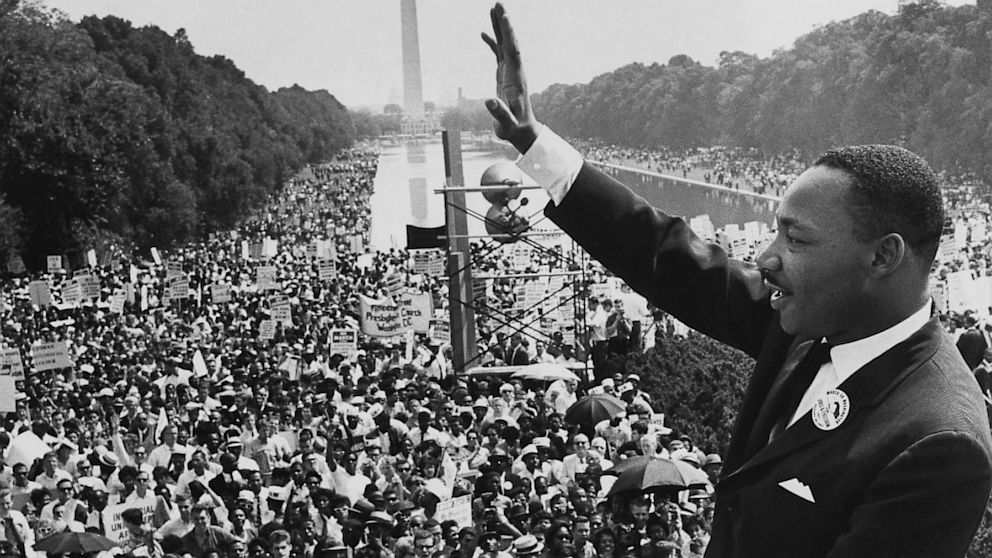

Throughout my childhood I had a vivid imagination and dream life. Like most kids, I developed the ability to have rich dreams that became increasingly complex. Thankfully, as these dreams increased in their complexity, rarely did they result in nightmares or night terrors. It wasn’t until my late teens that I realized how my subconscious mind through my dreams would solve problems I was presently faced with. If I were wrestling with a decision, it seemed that through an intense dream I’d receive the clarity I needed to make a choice. As a result, I’ve found that when faced with a personal or professional challenge — after sorting through the facts — more often than not, if I give my body and mind permission to rest, the solution will rise to my conscious mind. But, two years ago I stopped dreaming. Actually, I stopped recalling my dreams. Gone were the brilliant colors and picturesque scenes. Instead, I’d awake from hazy images of gray that I could not comprehend. My wild dreams that once served as a welcomed respite were no longer accessible. Psychologists note that dreams may be repressed due to trauma, stress, or anxiety. And, it seems the sudden loss of my father was the trauma that resulted in my inability to recall my dreams. My bold imagination had shifted dramatically. In truth, trauma may impact our psyche to the extent we experience heightened anxiety, increased irritability, lethargy, or emotional detachment. It can result in weight loss or gain or an increased vulnerability to fear. Trauma is real and its impacts cannot be underestimated. Then, we are challenged to consider how we promote national healing, racial reconciliation, and congregational health in trauma-filled communities. Trauma-filled communities — a designation slowly gaining credence among trauma experts — are communities categorized as having high crime rates and a lack of resources. As a result of deindustrialization, high local unemployment and political disenfranchisement, the landscape decays making life appear lackluster. The sight of trash-scattered sidewalks and abandoned buildings clouds the senses to the possibilities alive around residents. Indeed, dreams may be deferred because of personal, professional, or communal trauma. However, the biblical account of the character Joseph provides comfort for those who have lost the ability to dream or recall their dreams due to trauma. In the story, God dreams a dream in the young man living within a context that is not conducive for dream growth. He’s favored by his father and hated by his brothers. Tested in a context with an uneasy admixture of love and hate, he’s affirmed by the one from whom he came but rejected by his kin. Joseph is favored and hated. But, what God dreams through the favored-hated one is reason enough for us to celebrate. In his dream life he sees himself in a better state of being in comparison to his brothers and parents. Sadly, disgusted and intimidated by the possibility of the reality of his dream, his brothers hate and conspire against him as his father deflates his dreams of grandeur. That God would dream not one, but two dreams in a community that is unable to steward dream development is puzzling to me. Even more, that God would reveal divine plans in a climate where love and hate coexist, admittedly, causes me to question God’s methodologies. What is it about the soil of love and hate that serve as good ground for dream planting? With that, why would vivid imaginations and complex dreams arise within the company of dream snatchers? I contend dream snatchers are people who seek to undervalue the dreams of another person because of their own feelings of insecurity and fear. They are those who dismiss and crush God’s dream through someone else. Indeed, Joseph's family members were dream snatchers. The iconic “I Have a Dream Speech” delivered at the Lincoln Memorial by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., is both poetic and prophetic. Speaking poignantly to the injustices of his day, he grappled with the reality of the Emancipation Proclamation and the contradicting reality of the continued captivity of African-Americans as a result of segregation and discrimination. While the Declaration of Independence guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and pursuit of happiness, it seemed this was only extended to people were not of the African diaspora. It was in the soil of love and hate that God dreamed this dream in Rev. Dr. King Jr.. In other words, while the white majority loved how black mothers and grandmothers cared for their children, cleaned their homes, cooked their meal, and washed their clothes — they nonetheless hated their black skin. The soul in their voice and rhythm in their hips was welcomed entertainment, but the rich texture of black hair and resilience in their eyes was something to tame. Because the soil is still fertile with love and hate, oppression and injustice, God still dreams. Though we live in a present nightmare where George Zimmerman was acquitted in the murder of Trayvon Martin, and there were non-indictments in the deaths of Eric Garner and Tamir Rice, we continue to believe the dream God is dreaming in us. The nightmare began when our ancestors were stripped of their African garments, loaded on ships and packaged like sardines. The nightmare continued as those who survived the voyage across the Atlantic were sold as beasts on auction blocks. White supremacist ideologies want us to forget the atrocities of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. They want us to forget that we are haunted by the ghosts of cotton fields, slave quarters and lynchings. Sadly, this was no dream. Antagonists want us to forget those who were whipped, amputated, boiled in oil, separated and sold across the country. It’s prevailing principalities and powers that tell us to get over these injustices and atrocities. Get over Trayvon Martin, Sean Bell, Amadu Diallo, Mike Brown, and Sandra Bell, they contend. No! We can’t just get over these or any other lives stripped from our communities. For, these lives are buried in the soil of love and hate that give rise to our dreams of equality. Just like Joseph’s brothers who became intimidated by his dream, so has America become fearful of our rallying cry that, “Black Lives Matter.” Met with the rebuttal that all lives matter we’ve had to contend with modern day dream snatchers. As an African-American community we’ve had to steady ourselves in the face of well-intentioned but ignorant people. Yes, all lives do matter, and are created in the image and likeness of God. All lives matter — black, white, Hispanic, and Haitian, married, single, divorced, separated, heterosexual and homosexual, republican and democratic lives all matter. Nonetheless, when we cry “Black Lives Matter” it's not to subjugate any other race, but a reminder to oppressive systems that even if they don’t recognize God’s glory upon us, we do. It's a reminder to the world that we’re fearfully and wonderfully made. As Dr. King shared in this letter from the Birmingham jail, “There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair.” The rallying cry that black lives matter indicates the cup of our endurance has run over and God is dreaming a dream thru Millennials for this present age. The God given dream through Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is the same dream given to the world today. He or she who has an ear, let them hear what the spirit is saying. For the spirit speaks and dreams of a prison system that does more to rehabilitate inmates than use inmates as cheap labor. The spirit dreams through us of the deconstruction of institutionally oppressive systems that promote social, economic, housing and environmental inequities. As Rev. King said, “It is a historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntary give up their unjust posture; but as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.” Therefore, those living and working in the legacy and spirit of Rev. King must continue to dream and advocate for rights actions and outcomes concerning all citizens. This is the dream God continues to dream through us. Dawrell Rich is an author, pastor and public speaker. He is also the founder of Joshua’s House - a youth and young adult leadership organization that focuses on mentoring, community service, health & wellness and education. He has earned a reputation as a compassionate pastor, catalyst for change, and dynamic communicator.

For more information: www.dawrellrich.com Twitter: @dawrellrich FB: dawrellgrich This blog post is the first in a three part series from Jonathan Leonard, a doctoral student at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. The series will highlight the challenges presented by a history of racism in America, the church’s unique position to restore the broken relationship between God and humanity as a result of racism, as well as the church’s historical endorsement of the slave trade, and modern pastoral care practices that allow ministers to acknowledge, discuss, and listen to congregants in a sensitive fashion concerning this weighty issue. A new blog will be posted every month. We hope you will follow along and leave comments below. The image of God within people of African descent has been marred and consistently challenged from the beginning of the American experiment. This has been quite evident throughout the nation’s history. Yet the racism practiced in U.S. history can be seen as a manifestation of humanity’s fall in Genesis 3. In Genesis 1 and 2 God establishes order and proper relationship between Deity and creation and healthy relationships within the created order. Genesis 1:26-27 teaches that God created humanity in His/Her image and likeness. This endowed humanity with an innate dignity and a value. Every human regardless of gender, age, skin complexion, or physical ability is valuable. God gave humanity dominion over the animals of the earth, yet did not give humanity dominion over other humans. The desire to dominate fellow human beings came when humanity chose to move from a position of relationship with God to exultation and centering upon self. This was a veritable Pandora’s Box where sin in many forms manifested. Racism is one such sin that has particularly plagued humanity within recent centuries. Slavery throughout the millennia has had the pernicious characteristics of greed, brutality, and exploitation. The great Greek philosopher Aristotle stated this while questioning the humanity of slaves: For a man who is able to belong to another person is by nature a slave (for that is why he belongs to someone else), as is a man who participates in reason only so far as to realize that it exists, but not so far as to have it himself…other animals do not recognize reason, but follow their passions. The way we use slaves isn’t very different; assistance regarding the necessities of life is provided by both groups , by slaves and domestic animals. Nature must have intended to make the bodies of free men and of slaves different also; slaves’ bodies strong for the services they have to do, those of free men upright and not much use for that kind of work, but instead useful for community life.[1] Aristotle’s animalization of slaves is clearly dehumanizing. It seems to render them as tools, or rather some sort of animated tools. The same way a saw is the extension of its user, so the slave was an animated tool and extension of their master’s will. While slavery in the ancient world was clearly exploitative, it was also strangely egalitarian in that nearly anyone could become a slave in that world. An aristocrat whose city was conquered or an enemy combatant captured on the battlefield could easily become the property of their conquerors. Pirates swarmed the seas and routinely preyed upon ships, islands, and coastlines enslaving people in raids. In the Greco-Roman world, many nationalities and races were represented in the slave markets of the empire. Yet it was during the transatlantic slave trade that slavery would gain a racial component.[1] This would be the first time in Western history where a specific racial group of people became universally tied to perpetual bondage. David Brion Davis writes, “As slavery in the Western world became more and more restricted to Africans, the arbitrarily define black “race” took on all the qualities, in the eyes of many white people, of the infantilized and animalized slave.”[2] The Avalanche The challenge to the image of God in people of African descent in America continues this day and can be witnessed in the various forms of police brutality. In June of 2015 in Austin, Texas, a police dashcam captured a white Austin police officer slamming a slender African-American woman to the ground. The woman’s name was Breaion King, a twenty-six year old elementary school teacher. She was pulled over for speeding, but things quickly escalated which led to her being slammed to the ground and handcuffed in the back of a squad car. Yet it was King’s interaction with another officer in the vehicle that seemed to raise eyebrows even further. King questioned the officer: “Why are you all afraid of black people?” The officer then replied to King’s question stating blacks have “violent tendencies” and “intimidating” appearance. He went on further to state: “Ninety-nine percent of the time … it is the black community that is being violent,” the officer told her. “That’s why a lot of white people are afraid. And I don’t blame them.”[3] These comments started an avalanche in my mind concerning racism, American history, the image of God, and the role of religion in justification of slavery. These comments from the officer are a manifestation of generations of thought formulated in the realms of politics, economics, law, science, and religion. Many Americans are woefully ignorant of the basics of U.S. history such as naming the victorious side in the Civil War, who the U.S. gained independence from, or naming the vice-president.[4] This presents a greater challenge to understanding the historical underpinnings of white supremacist thought and how it undermines the ideals espoused by the country’s founders. How does this link to understanding the image of God and slavery? In the encounter between King and the officer, was the image of God exulted or diminished? (When I refer to the image of God, it is in reference to the image of God in Breaion King and the officer who slammed her as well as the officer who made those comments about African-Americans). Continued...This blog post is the first in a three part series. Read the entire series here: A Diminished Image of God in Europeans, Part II The Image of God and Slavery in America, Part III [1] For more elaboration on the shift from slavery being a status that nearly anyone had the possibility of falling into to the racial component later imposed by Western nations on Africans see David Brion Davis, In the Image of God: Religion, Moral Values, and Our Heritage of Slavery. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001. See also Milton Meltzer’s work, Slavery: A World History. Chicago: Da Capo Press, 1993. [2] Davis, 128. [3] Michael E. Miller, “Austin police body-slam black teacher, tell her blacks have ‘violent tendencies,” (22 July 2016) https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/07/22/video-austin-police-body-slam-black-teacher-tell-her-blacks-have-violent-tendencies/ (10 August 2016) [4] Americans of all ages seem to fail to answer basic questions about U.S. history. A 2008 study by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, which surveyed more than 2,500 Americans, found that only half of adults in the country could name the three branches of government. The 2014 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) report found that only 18 percent of 8th graders were proficient or above in U.S. History and only 23 percent in Civics. (Saba Naseem, “How Much U.S. History Do Americans Actually Know? Less Than You Think.” Smithsonian Magazine http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-much-us-history-do-americans-actually-know-less-you-think-180955431/ (10 August 2016). Jonathan Leonard currently works for Safe Alliance, a 501(c)(3) based in Austin, Texas, which serves victims of domestic violence and children who are victims of neglect and abuse. Jonathan has worked in the non-profit realm with at-risk youth for nearly 10 years. He holds an M.Div and M.A. in Biblical Literature from Oral Roberts University. He is currently pursuing doctoral studies at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. He resides in the Austin area with his wife Tausha and three children, DeAnnah, Jonathan Jr., and Justin.

ICTG welcomes guest blogger, Rev. Shaun Lee, pastor of Mount Lebanon Baptist Church, Brooklyn, NY, sharing about congregational responses to the 2014 Eric Garner killing in New York City. Thousands of people around the globe filled city streets with banners and signs chanting "I can't breathe" in response to a grand jury's decision to not indict New York City police officer Daniel Pantaleo for the killing of Staten Island resident Eric Garner. It was a decision that was highly anticipated given the backlash for a lack of indictment of another policer officer in Ferguson, Missouri for the killing of a young unarmed black male named Michael Brown. New York City especially felt the effects of this decision with protesters walking the streets for several successive evenings in an effort to disrupt traffic and city logistics with an understanding that if the citizens could not get justice, then the city would not get peace. Police presence was heavy, but they were given instructions to allow peaceful protests to go unobstructed. The mayor's empathetic tone for protestors put police officers on edge. During this turmoil another police officer shoots an unarmed black male named Akai Gurley as he was walking down the stairs of his building. Tensions rose throughout the city and just when things were reaching its peak two NYPD officers were shot while sitting in their patrol car by a man who claimed to be exacting revenge for the recent victims of police killings. All of this happens within a span of 17 days and the question is how does the church engage in the healing process when so much community trauma has taken place. My congregation, and several others have chosen to engage in protest, prayer, and partnership as a way of promoting healing and peace within our congregations and community. After the decision of the grand jury to not indict officer Pantaleo several Brooklyn pastors joined together in an effort to create a space for the church to practice peaceful protest for those who could not and would not join in the late night protest. This was a particularly sensitive issue because several members of the congregation are police officers, but in dialogue with them and other officers I felt confident in promoting this protest without the fear of it seeming anti-police. We ended service early and marched with several other congregations within the community to express our discontent and to stand in line with the rich history of the African American church of speaking up to issues of injustice. As we marched onlookers within the community joined our walk, sang beside us, and prayed with us. Since prayer is a tool for transformative power the march ended with a prayer rally. Congregations had been praying on their own, but it was important to pray together as a part of the larger community. It was a great moment for the community and a call to action for the churches within the community to continue experiences like this. We were called to do it again after the shootings of Officers Rafael Ramos and Wenjian Liu, the two officers shot in their patrol car. The shape of it changed in that it was a prayer vigil for peace and justice. We were careful to be sensitive to the police officers during their time of grief while also keeping in mind that justice was still at the forefront of the discussion. Eric Garner's sister, Ellisha Flagg, also joined us in our call for peace and spoke to all those gathered. This rally was planned in partnership with our local councilman and police precinct. Some officers from the community affairs bureau of our local precinct marched with us as we continued to try to bring healing to our community after so many devastating events began to take its toll. We prayed together for the victims of senseless violence, the safety of police officers, the relationship between the mayor and the NYPD along with the relationship between the community and NYPD. It was a sobering reminder that in the grand scheme of things all lives truly do matter and have value in the sight of God. A powerful moment occurred when one of the pastor's read the names of those who were killed in our community to violence in the past year. As each name was read and single white ballon was released into the sky. Certainly the need for continued healing is important. The local congregations have decided to continue partnering together to create experiences that foster healing and prayer. We have also decided to partner with the local police precinct and elected officials to create dialogue and ensure that the community still has a say in policy and how it is policed. Needless to say these partnerships already existed but trauma has a way of reshaping and remodeling our current practices. Through continued dialogue we are better able to deal with traumatic issues when they arise instead of being reactionary. Rally NY Dec 2014 // photos courtesy Rev. Shaun Lee Reverend Shaun J. Lee, a Brooklyn, New York native, serves as the seventh pastor of the Mount Lebanon Baptist Church. His ministry focuses on getting individuals to establish a true relationship with Christ, establishing a meaningful membership in God’s church and a concrete connection with the surrounding and global community. Reverend Lee firmly believes that the Word, Worship, and Work are central to advancing the Kingdom of God. An active member of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc., Reverend Lee aims to connect with the un-churched through various pillars he’s set in place. Staying in tune with his own personal passions of social justice, he crafted institutions to reflect his ministry including a monthly soup kitchen, back-to-school BBQ that provides 500 children with supplies, a strong social media presence led by volunteers from the congregation and the Judges 19 Ministry which focuses on helping both men and women victimized by domestic abuse. Reverend Lee is married to Valerie, and delights in the nurture of their daughters Sian and Sanai.

|

�

CONGREGATIONAL BLOG

From 2012-2020, this blog space explored expanding understanding and best practices for leadership and congregational care.

This website serves as a historical mark of work the Institute conducted prior to 2022. This website is no longer updated. Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed